The catastrophic fires that have struck the U.S. states of California, Oregon, Washington, Colorado, New Mexico and Arizona in recent years are proving to be part of a new era and no longer isolated occurrences. While not as prominently reported, this theme has been repeated throughout the West, including Idaho, Wyoming, and Montana.

When catastrophic fires occur, it is evident the fire-risk regime utilities operate in has changed significantly. Utility vegetation managers must fully assess and comprehend the risks and how quickly risk is changing to be successful in managing infrastructure and vegetation to protect it from fire and ensure ignition risks are removed from the system.

Western Fire Risk

As Western droughts persist and vegetation continues to be inadequately managed across the landscape, pandemic population shifts have complicated the risk equation. According toa study published on Dec. 8, 2022, in the Frontiers in Human Dynamics journal, Flocking to Fire: How Climate and Natural Hazards Shape Human Migration Across the United States, more people call the interior West their home now, and the result has been an expanded wildland-urban interface (WUI), significantly increasing the population and number of structures at risk from wildfire.

For example, in Santa Fe County, New Mexico, where about 155,000 people reside, more than 34,000 private properties are at high risk of catastrophic fire, according to the Insurance Journal. So, even though New Mexico does not have as large of a population as California, a high proportion of its

population is at risk.

This population expansion into rural areas further complicates fuel treatment where a century of fire suppression and management policies has resulted in a highly combustible buildup of dead and live fuel. Utilities also are under increased pressure to provide highly reliable electric service to meet the demand of the shifting population of remote employees working from their homes.

While no one can put a value on life, there are quantifiable costs to loss of structures and fire suppression. For example, 2021 marked the most expensive year for annual federal suppression, with costs nearing US$4.5 billion, according to the National Interagency Fire Center. Property values have risen dramatically, with some Western states experiencing 40% increases in property value since summer 2020, according to the U.S. Census Bureau and U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. As property values have dramatically increased in some Western states, it is presumed that costs associated with fire risk will only increase in future fire events. The values associated with fire risk today are vastly different than those from merely two years ago.

Utility-caused fires have been exceptionally destructive to life and property in recent years. Despite utilities’ efforts to manage grow-in risk and hazardous trees, danger-tree failure-related electrical ignitions continue to occur — with devastating impacts. Consider the Dixie Fire in California that raged across five counties from July 13, 2021, until it was declared contained on Oct. 24, 2021. All told, more than 963,000 acres (389,712 hectares) burned, with one fatality and about 1500 structures lost. The fire was the first to cross the Sierra Nevada — and it did so twice. The cause of the Dixie Fire is alleged to have been a tree failure resulting in contact with energized conductors.

Across the West, regulators have begun requiring utilities — from the largest investor-owned utilities to the smallest electric cooperatives, to document and submit their plans to reduce wildfire risk. Where this has not occurred yet, it is likely to soon and with good reason — because the risk of a catastrophic wildfire occurring and the losses associated with a fire have both increased dramatically, not to mention the significantly increasing insurance premiums.

Utility Fire Risk

For utilities, wildfire risk is essentially made up of two components:

1. Ignition risk, or a fire caused by the utility’s assets

2. Carry risk, or the risk to the utility’s infrastructure when a fire threatens that infrastructure while being carried by adjacent fuel and weather regimes.

Fire contains three basic elements: heat (ignition source), fuel and oxygen. Utilities can manage vegetation to control two of these elements, a heat source and fuel, near utility infrastructure. In other words, ignitions occur when a heat source contacts fuel. Utilities can prevent this from occurring in two ways through vegetation management practices:

1. Prevent infrastructure failure (engineering solution), including tree-caused infrastructure and equipment failure

2. Reduce the likelihood of ignition by removing fuel around the infrastructure in the event a failure occurs.

Going a step further, utilities also can control fuel around or adjacent to infrastructure — mostly vegetation in the West — to protect the infrastructure and nearby communities from an advancing fire.

Two Approaches

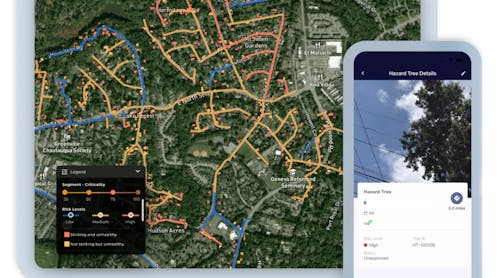

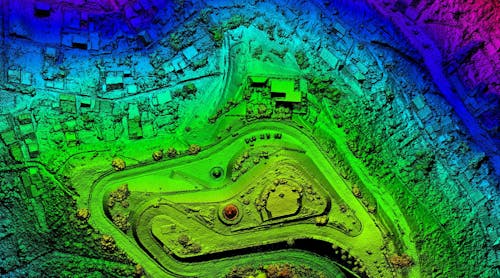

One approach to vegetation management is to make decisions following a risk management framework. Determining which vegetation to control is site specific, but the good news is numerous data sets are available and becoming less expensive over time, including remote sensing, light detection and ranging (LiDAR) and other emerging technologies.

The data sets provide objective information about vegetation and its proximity to infrastructure, but the management decision to apply prescriptions rests with decision makers after evaluating qualitative information and risk tolerance.

A second approach is to manage vegetation to tree height to achieve the lowest level of risk. All vegetation within strike height is removed. Some utilities are embracing this approach, which seemed far-fetched only five years ago.

With the managing-to-tree-height method, any tree tall enough to strike infrastructure is removed, and the zone along the infrastructure is managed thereafter to keep low-growing vegetation under and near the infrastructure — with ongoing integrated vegetation management (IVM) entries and techniques coupled with encroachment prevention.

To gain long-term risk reduction, encroachment prevention also must occur, including regular reentry to capture trees that have grown tall enough to strike facilities, perhaps as often as every 10 years to 15 years, depending on growth rates. This work should be done in conjunction with integrated management activities that minimize vegetation fuel near infrastructure.

Real-World Example

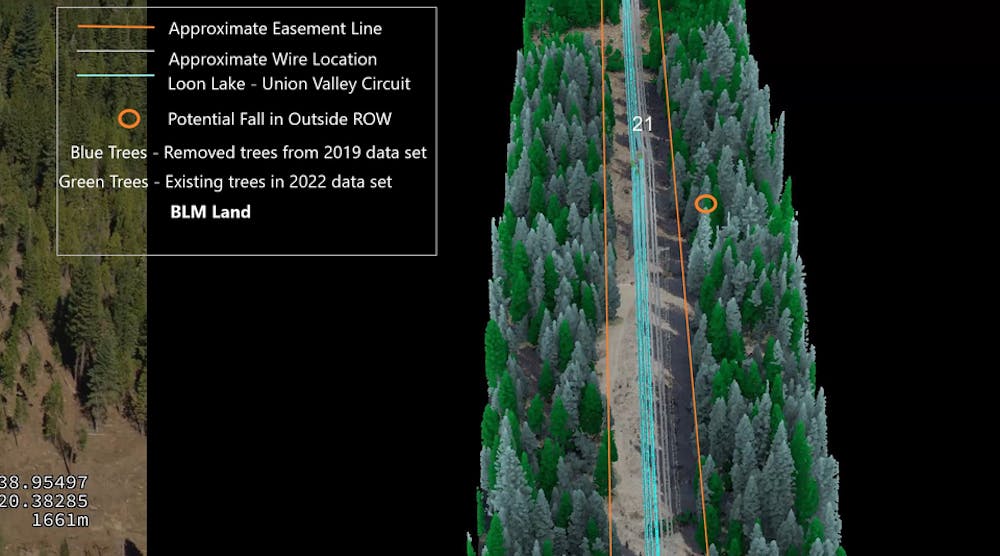

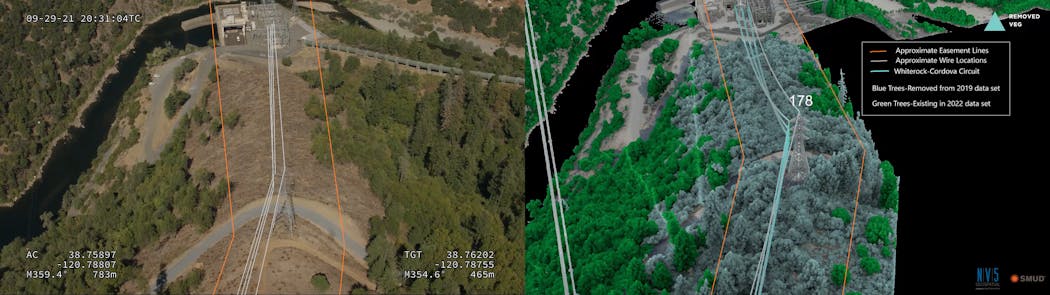

The Sacramento Municipal Utility District (SMUD) has been a leader in using technology to identify trees that constitute a risk to its infrastructure. In one case, it used remote sensing and LiDAR along the rights-of-way to detect trees tall enough to strike infrastructure. SMUD also is in the process of thinning the area along the infrastructure to create a shaded fuel break.

It is noteworthy to point out this work was conducted on federal lands, and partners at the agencies took a leadership role with SMUD to conduct work that would meet both parties’ objectives.

Engineering Benefits

Utility vegetation managers have long recognized the multiple benefits derived from vegetation management that support the engineering and equipment elements of fire mitigation plans. Concentrated, strategic vegetation management changes the fire environment and resultant engineering and equipment requirement — to the benefit of the utility and surrounding communities. With more outreach and education, utility engineers and maintenance managers may recognize the benefits and forge strong relationships with vegetation managers for mutual benefit.

Opportunities Throughout The West

Throughout the West, there are plenty of locations where managing vegetation near infrastructure to tree height can and should occur. The barriers to doing work like this are formidable but slowly coming down because proponents and opponents of vegetation management are aligned in their opposition to wildfire and understand the wildfire risk profile of the West must change.

One company with experience managing vegetation to tree height for Western utilities is JH Land Consultants. Its approach to vegetation management focuses on reducing both the ignition and carry components that make up wildfire risk while rendering landscape-level results in a cost-effective way. The company offers turnkey solutions, project by project, that provide utility rights-of-way with little or no risk of vegetation interactions with infrastructure and vegetation fuel loads/regimes that are likely to cool off a fire, slow it down and even stop it under the right conditions. In addition, it specializes in selling the timber produced during vegetation management activities to generate funds and offset costs.

With more utilities starting to embrace the practice of managing vegetation to tree height, it is time for vegetation managers to consider how this approach could help to lower risk of wildfires along their utility’s T&D systems.

Niel Fischer ([email protected]) is a registered professional forester and attorney at law with 35 years of experience in private forest management, utility vegetation management, law and policy. From July 2019 to July 2022, Fischer managed operations on 191,000 acres (77,295 hectares) in California and Oregon and sourced two sawmills. From 1990 until 2005, he practiced nonindustrial forestry throughout northern California on ownerships ranging in size from 3 acres to over 35,000 acres (1.2 hectares to over 14,164 hectares). Fischer spent more than 13 years in between his forestry work at Pacific Gas & Electric Co., where he developed its hazardous tree rating system and authored its vegetation management rate cases. He also is a contributor to the ANSI A-300, Part Nine, Hazardous Tree Arboriculture Standard Best Practices companion publication.

Eric Brown ([email protected]) is manager of the vegetation management department at Sacramento Municipal Utility District (SMUD). He is a Certified Arborist, TRAQ certified and a past president of the Utility Arborist Association. Brown has his bachelor’s degree in forestry and range management from the University of Nevada, Reno. He is a director of the El Dorado Fire Safe Council and deeply connected to the people and resources of central California. Brown has over 25 years of experience in the utility vegetation management profession, mostly in northern California where he has witnessed firsthand how fire risk has changed.

Editor's Note: SMUD will be the utility host for T&D World Live 2023 in Sacramento, California, on Sept. 12-14. For more information, see our conference site.